Ernesto’s Graded Books

Ernesto Method 2025

Ernesto Method 2024

Ernesto Method 2023

Basics on ESL

The Basics on ESL

In the Basics on ESL you will find a variety of books that will help you through your journey.

After reading “The Basics on ESL”, you can check important issues for ESL teachers on the section PDFs, and visit my channel on YouTube.

The Ultimate Teaching ESL Book of Speaking Activities is a resource pack containing roleplays, problem solving activities, questions, visual materials and a whole host of other stuff to make your classes special.

Cool Kids Speak English – Book 1: Enjoyable activity sheets, word searches & colouring pages for children learning English as a foreign language. With fun activity sheets, great word searches & lovely coloring pages, Cool Kids Speak English Book 1 is an ideal book for children learning English. The suggested age range for this book is 7 to 11 year olds, but the fun activities may also interest children of other ages. The topics in book 1 include Numbers 1-10 – Greetings – Colors – Animals – Clothes – Weather.

Incredible English 1. 2nd edition. Class Book. This great new introduction to the 6-level Incredible English series is a completely wordless course book. The course supports an aural-oral introduction to English, for children who are not yet ready to start reading and writing in English. With 60 hours of material, Incredible English Starter aims to bridge the gap between pre-school and primary school and develops their understanding of the world and social skills along with their English language learning.

Second Grade Phonics and Spelling (Highlights Learning Fun Workbooks). Phonics and spelling are important building blocks for future learning, and Highlights (TM) brings Fun with a Purpose® into these essential activities for second graders. Our award-winning content blends important language skills with puzzles, humor, and playful art, which makes learning exciting and fun. Students will learn developmentally appropriate vowel and consonant patterns, spelling strategies, decoding skills, and more – all designed to help improve and build confidence in the classroom.

Key Methods in Second Language Acquisition Research is a book written to help novice teachers and undergraduate students developing an awareness and understanding of the key methodological frameworks and processes used in second language research. The book should also help readers generating ideas and researchable questions and adopting particular research methods and procedures to collect and analyse data. The book is divided into three main parts: Key Stages in Second Language Research, Key Methodological Frameworks, and Mixed Frameworks and Psycholinguistics Methods.

How Languages are Learned – This easy-to-read introduction introduces the most important theories on first and second language acquisition and explains their practical application in class. In this way, teachers can better assess the advantages of different methods and make optimal use of the time with their students. The completely revised practical part takes into account the wide variety of ethnic, cultural and linguistic backgrounds of the learners.

Linguistics for Language Learning: An Introduction to the Nature and Use of Language. This book is first and foremost for learners of another language and their teachers. It is also for future language teachers. In a more general way it is for anybody who would like to know more about the nature and use of language, especially as it is manifesting itself across the obvious differences between languages.

What Teachers Need to Know About Language – Rising enrollments of students for whom English is not a first language mean that every teacher – whether teaching kindergarten or high school algebra – is a language teacher. This book explains what teachers need to know about language in order to be more effective in the classroom, and it shows how teacher education might help them gain that knowledge. It focuses especially on features of academic English and gives examples of the many aspects of teaching and learning to which language is key. This second edition reflects the now greatly expanded knowledge base about academic language and classroom discourse, and highlights the pivotal role that language plays in learning and schooling. The volume will be of interest to teachers, teacher educators, professional development specialists, administrators, and all those interested in helping to ensure student success in the classroom and beyond.

Key Issues in Language Teaching – A comprehensive and extensively researched overview of key issues in language teaching today. This essential text for English language teachers surveys a broad range of core topics that are important in understanding contemporary approaches to teaching English as a second or international language, and which form the content of many professional development courses for language teachers. A wide range of issues is examined, including a consideration of the nature of English in the world, the way the English teaching profession works, the development of teaching methods, the nature of classroom teaching, teaching the four skills, teaching the language system, and elements of a language program.

Teaching Languages to Young Learners – Recent years have seen rapid growth in the numbers of children being taught foreign languages at younger ages. While course books aimed at young learners are appearing on the market, there is scant theoretical reference in the teacher education literature. Teaching Languages to Young Learners is one of the few to develop readers’ understanding of what happens in classrooms where children are being taught a foreign language. It will offer teachers and trainers a coherent theoretical framework to structure thinking about children’s language learning. It gives practical advice on how to analyse and evaluate classroom activities, language use and language development. Examples from classrooms in Europe and Asia will help bring alive the realities of working with young learners of English.

Research Methods in Applied Linguistics is designed to be the essential one-volume resource for students. The book includes: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods; research techniques and approaches; ethical considerations; sample studies; a glossary of key terms; resources for students. As well as covering a range of methodological issues, it looks at numerous areas in depth, including language learning strategies, motivation, teacher beliefs, language and identity, pragmatics, vocabulary, and grammar. Comprehensive and accessible, this is the essential guide to research methods for undergraduate and postgraduate students in applied linguistics and language studies.

Key Questions in Language Teaching: An Introduction – Innovative and evidence-based, this introduction to the main concepts and issues in language teaching uses a ‘key questions’ structure, enabling the reader to understand how these questions have been addressed by researchers previously, and how the findings inform language teaching practices. Grounded in research, theory and empirical evidence, the textbook provides students, practitioners and teachers with a complete introductory course in language teaching. Written in a clear and user-friendly style, and avoiding use of jargon, the book draws upon real-life teaching experiences and scenarios to provide practical advice. A glossary of key terms, questions for discussion and further reading suggestions are included. The book is perfectly suited to language teaching modules on English language, TESOL and applied linguistics courses.

Language in Education: Social Implications – Teachers in any subject area must have a basic understanding of how language is learned and used in educational contexts because language impacts teaching and learning across all subjects. This book is written specifically for those teachers and teacher traineeslearning to teach who want to know more about language learning and use in educational contexts and, especially, those who care about the social implications of language in education. Chapters address crucial questions that teachers must address: How is language structured? How is language learned at home and in school, by first, second and bilingual language learners? How is language used in classrooms to shape learning? How does language vary in different regions and due to social characteristics of users? How can language be used to make meaning in different modes (oral/written) and contexts? How do language policies intersect with education policies, and how do these impact teachers? The chapters are full of examples of language use in educational contexts to help readers understand language in action. The examples not only highlight key points, they also provide opportunities for readers to deepen their understanding by experiencing analysis of language. Each chapter closes with a discussion of relevance to educational settings and questions which can be used for in-class discussion or personal reflection. Suggestions for further readings and online viewing are included, and a comprehensive companion website is available.

Language Teaching: Linguistic Theory in Practice – How can theories of language development be understood and applied in your language classroom? By presenting a range of linguistic perspectives from formal to functional to cognitive, this book highlights the relevance of second language acquisition research to the language classroom. Following a brief historical survey of the ways in which language has been viewed, Whong clearly discusses the basic tenets of Chomskyan linguistics, before exploring ten generalisations about second language development in terms of their implications for language teaching. Emphasising the formal generative approach, the book explores well-known language teaching methods, looking at the extent to which linguistic theory is relevant to the different approaches. This is the first textbook to provide an explicit discussion of language teaching from the point of view of formal linguistics.

A Course in Language Teaching: Practice and Theory: Practice of Theory -This important new course provides a comprehensive basic introduction to teaching languages, for use in pre-service or early experience settings. It can be used by groups of teachers working with a trainer, or as a self-study resource. It consists of modules on key topics, arranged into sections covering: The Teaching Process, Teaching the Language, Course Content, Lessons, and Learner Differences. Modules can be used in sequence, or selectively. Each module presents practical and theoretical aspects of the topic, with tasks. Suggestions for classroom observation and practice, action research projects and further reading are included. Notes for the trainer with stimulating insights from the author’s personal experience complete the course.

Language Assessment in Practice – Presents an innovative, unified, and easily applied approach to designing and developing language assessments. Language Assessment in Practice is a follow-up to the bestselling Language Testing in Practice. It allows readers to become competent in the design, development, and use of language assessments. The authors discuss concepts and procedures clearly, illustrated with examples.

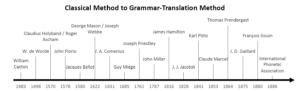

The Classical Method

To understand the Classical Method of English Teaching, it is important to take a look at Anthony Philip Reid Howatt, A History of English Language Teaching (1984), in it he presents an overview of the historical developments of ESL teaching. The book provides great insights into the views and beliefs held by content creators, teachers, linguists, and even psychologists when dealing with the subject matter. It clarifies that many of the present-day concerns in English language teaching are not exceptionally new-found and that tradition has been one of the main guiding principles. After describing how methods are built, it is crucial to take a step back and examine how ESL teaching has been conducted since its initial stages in the early modern period.

After reading “The Grammar Translation Method”, you can check important issues for ESL teachers on the section PDFs, and visit my channel on YouTube.

According to Howatt, in the sixteenth century, English was the main language of England, French was a prominent deed, and while Latin lingered as the symbol of an enlightened person, its grammar was the only one taught in school. It was not until the seventeenth century that a scholarly description of the English language was produced. In the lack of a syntactical account of the language, old language teaching materials, predominantly dependent on texts and dialogues, were transformed for the teaching of English. Dialogues were a deep-rooted convention in Latin teaching, in addition to question-and-answer techniques. These techniques came from a previous teaching design, regular in orate groups, where the objective was to learn literally written texts by heart (Howatt, 1984, pp. 3-6). Joseph Priestley’s The Rudiments of English Grammar written in 1761 is a late but conventional model where it shows how the Classical Method made students put tremendous effort into memorization while the teacher only had to sit down and purely ask them the questions. A good example from the book on page 13 illustrates this. The teacher would ask “What is a verb?” and the students would answer “A Verb is a word that expresseth what is affirmed of, or attributed to a thing; as I love; the horse neighs” (Priestley, 1772, p. 13). The teacher would again question the students “How many kinds of verbs are there?” and once again the students would answer “Two; Transitive and Neuter” (Priestley, 1772, p. 13). At the end of the sixteenth century, the first ESL textbooks appeared, thanks to French refugees (Howatt, 1984, p. 6).

Howatt suggests that an appeal in learning the language appeared among people of the trade section. Double-manuals seeking to teach English to French people and French to English people start flourishing. William Caxton, a member of the trade community in Bruges, organized and printed in 1483 a double-manual. His manual endorses the previous manuals, though it is bilingual and direct, not containing any linguistic information about either language. It has household tools, shopping lists (with typical stuff you find on a market), a dialogue about selling and buying textiles of various types, words describing family relationships, etc. in summary texts intended toward vocabulary building for students. What is most fascinating about Caxton’s manual is that he brings the L2 next to the L1. The following dialogue is a good example of this (Howatt, 1984, pp. 6-7).

A vostre pere et a vostre mere, To your fadre and to your modre,

A vostre tayon et a vostre taye, To your belfadre & to your beldame,

A vostre onlce et a vostre aunte, To your eme & to your aunte,

A vostre cosyns et a vostre cosynes, To your cosyns and to your nieces

(Caxton, 1483, p. 6)

Caxton is the first one who analyzed that daily language should be taught and that L2 should be given the same status as the L1. He puts the original text and the translation in the same line, which is less useful than what Caxton’s assistant, Wynken de Worde did only 15 years later. He produced a similar double-manual called A Lytell treatyse for to lerne Englysshe and Frensshe (c. 1498). Contrary to his former boss, de Worde set the L2 and the L1 in interchanging lines (Howatt, 1984, pp. 7-8). The presumption is, that it makes a word by word translation much easier.

Here is a good boke to lerne to speke Frenshe

Vecy ung bon livre apprendre parler françoys

In the name of the fader and the sone

En nom du pere et du filz (de Worde, c. 1498, qtd. in Howatt 1984, p. 8)

Signs of a flourishing interest in the English language can be noticed in the form of multilingual dictionaries and phrasebooks that started to incorporate English as one of its main languages. The earliest is a 1540 dictionary, published in Antwerp, called the Alston Bibliography which contains seven languages: Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, Dutch, High-Dutch, and English (Howatt, 1984, p. 8).

Howatt further states that in 1572, French refugees settled in England, and among these refugees were teachers. Three of these teachers made themselves noteworthy, namely Jacques Bellot, Claudius Holyband, and John Florio. Florio and Holyband were native speakers of the L2 they taught but kept teaching the traditional bilingual way. The two small English manuals that Jacques Bellot wrote in the 1580s, The English Schoolmaster (1580) and the second book Familiar Dialogues (1586) reflect an important insight into basic literacy and daily dialogues. In the Schoolmaster, Bellot presents the English alphabet, pronunciation, some grammatical issues, and words that students would have some difficulty with, such as “hole/whole, bore/boar, horse/hoarse or common ambiguities such as right, straight, and hold” (Howatt, 1984, p. 16). Presenting these words and clarifications in print provided insight to the students that had only learned the language in the streets (Howatt, 1984, pp. 12-16). His second book focuses more on a household environment, particularly shopping. He presents a long sequence of shopping scenes that last the course of a single day. After waking up and preparing the kids for school, the characters then drop by common shops, ending the day by having the neighbors over for dinner. The conversation during dinner focuses on recent topics and later the characters play games. What makes it important to ESL teaching is the fact that at in all these events, he incorporated a rough phonetic note of the L2 texts (Howatt, 1984, pp. 16-19). The Classical Method of English Teaching was growing.

According to Howatt, Claudius Holyband wrote two major textbooks, The French Schoolmaster (1570) and The French Littleton (1573). The two are also teaching manuals, and both adopt dialogues. The main distinction between these two books and Bellot’s is that it contains instruction on grammar and pronunciation. The Schoolmaster brings this information early and the Littleton in its appendix. They also have a vast vocabulary list. Holyband’s dialogues are presented like Bellot’s daily life situations, where considerable scenes are presented in sequence. These scenes come from many different backgrounds. One for example is school, and according to Howatt, they served their educational purpose quite well. Every scene is comprising of enough material for one lecture while keeping the context from one class to the next. The students read the text out loud, repeating it until they reached a fair pronunciation. Subsequently, the children wrote down the text from the L1 to the L2 and then from the L2 to the L1. Regarding grammar, Holyband consulted grammar rules only after the students had a very good comprehension of the texts. For him, grammar only fits in a more elaborate course (Howatt, 1984, pp. 21-24). In this stage the Classical Method of English Teaching was been drastically changed from its roots in classical literature.

Howatt describes the third of these refugee-teachers, John Florio, as someone who interprets language teaching differently. His two double-manuals, First Fruits (1578) and Second Fruits (1591) include dialogues in Italian and English. They contain, as the two authors before, something that later would come to be considered very important to future methods: situational themes. Situations such as getting accommodation and being in contact with a landlord are examples of that. As an intense student of language, Florio gathered lexicographical works and many proverbs in his books. The interesting takes from Florio’s works are the situational themes, the use of proverbs, and golden sayings. These aspects later, by the use of chunks, became essential to future methods (Howatt, 1984, pp. 25-27). The Classical Method of English Teaching is the base for all ideas that came.

Howatt continues his analysis, and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, a tradesman from France called George Mason composed a handbook with the name Grammaire Angloise (1622). In it, he presented rough phonetic transcription of the conversations. What makes this important is that he gives notability to the verb form, progressive or continuous. This shows how the teaching and analysis of English grammar were growing apart from its Latin route (Howatt, 1984, pp. 29-30).

According to Howatt, a clear change in classrooms happened during the seventeenth century, a period where most young children attended grammar school to obtain elementary instruction on their L1. These students were immediately conditioned by Latin grammar books with no alternative but to memorize its rules and definitions, and if that did not occur, they risked physical repercussions. So, in such circumstances, many new and different ideas started to emerge during this period. The only thing that brought these new ideas together was the preference of text rather than rules. A good example is Roger Ascham’s book The Schoolmaster (1570) (Howatt, 1984, pp. 32-33). Howatt describes Ascham’s Schoolmaster as a book directed exclusively to the education of a specific child, and that it is divided into two parts. The first part is named The Bringing Up of Children where he discusses the education, the reasons, and the goals of a noble child. He believed that by presenting the child with the ancient literature, it would eventually spark understanding and culture upon that child. In The Ready Way to the Latin Tongue (the second part of his book), he explains how to achieve the educational goals of the first part, within a pedagogical curriculum. The “double-translation” is the most popular procedure, where Ascham gives L1 and L2 the same status, helping the student understand the structure of the L1 and the L2, by presenting the L2’s literature (Howatt, 1984, pp. 33-34). This literature is one of the main aspects of the Classical Method of English Teaching.

According to Howatt, Joseph Webbe designed a language textbook called An Appeal to Truth (1622), in which he removed grammar altogether. He believed that grammar rules were inadequate in their portrayal of language and that by studying them, the students would lose valuable time. He then focused on exercising communication skills, believing that these skills would eventually lead to an understanding of grammar. He also believed that translation was important in L2 vocabulary building, but he did not agree with L2 word-by-word translation to L1, holding the belief that translation equivalence existed only at the level of the construction. He conditioned his method to this perception. Howatt brings Webbe in the same line, with the conditions of the later known Direct Method (Howatt, 1984, pp. 35-37).

As attested by Howatt, Jan Amos Comenius wrote two books, the Janua Linguarum Reserata (1631) and the Orbis Sensualium Pictus, published in Nuremberg in 1658. He saw education in an extremely specific way and used the metaphor of the Temple for his educational stages. The first stage was Vestibulum, the second Janua, the third Palatium, and the fourth Thesaurus. He visualized two textbooks, each with four stages (according to the temple stages). The first important observation regarding Comenius’ work towards a better language teaching method is that in the Vestibulum, which only had a few hundred words designed for simple daily conversations, he added a list of additional words, acknowledging which words to focus on. In the Janua he increased that emphasis by essentially creating a school textbook central to the teaching of 8,000 words in a sequence of graded texts with a small dictionary being attached. The Palatium, which never came to light, was supposed to introduce the accurate use of language and style. Lastly, the Thesaurus, which also never came to light, would have been largely dedicated to the contrasting characteristics of the L1 and L2, and of course, translation. Comenius did not make great progress with his method, but he did come up with insights. In the Vestibulum he arranged Latin texts side-by-side to other languages in text. Another great insight of Comenius is that he started the section The Accidents of Things that focuses on teaching basic nouns by employing short constructions such as “The grass is green, The chimney is full of smoke” (Howatt, 1984, p. 42) and so on. The section called Things Concerning Actions and Passions focuses on verbs in the simple present tense. Circumstantial Things focuses on prepositional phrases and adverbs. And the final chapters address vocabulary building. He captured all the words he used in the texts and placed them in the Index Verborum. The Solid Things part is where he ordered in different topic categories, one hundred texts. The texts were short so the teachers could address them slowly in class and as a teacher Comenius knew that having the children around him, an early teacher-centric view of the classroom, made it easy for him to handle the class. He started every class focusing on the short text and only went on when he was certain that the students had grasped the content of the text (Howatt, 1984, pp. 40-44). Howatt continues his description of Comenius and his second book, the Orbis Sensualium Pictus. Here, Comenius makes usage of another great process in language teaching. He started each Orbis lesson with a picture which was linked to the words in the text. This shows that providing more input for the creation of a memory helped the students remember the words easier. In his view the teacher should start each class addressing the picture, and, when available, the teacher should provide the real object to the students. Not satisfied with it, he went a bit further and suggested that the students could draw or color the objects themselves. He also believed that the students could disclose their personal lives, feelings, and ideas in the classroom. Most of Comenius’ suggestions were picked up for my preferred teaching approach (Howatt, 1984, p. 46).

In the second half of the seventeenth century, according to Howatt, a requirement for French native-speaking teachers arose in Britain and the Classical Method of English Teaching was being used but with no name. These French speaking teachers not only did their jobs, but they also focused on teaching ESL to the French-speaking refugees who were living in Britain at the time. There was a Swiss man among these French teachers named Guy Miège whose Nouvelle Méthode pour apprendre l’Anglois (1685) elevated the teaching of English as a foreign language to a professional standard. His Nouvelle Méthode was published by him and translated into English as a non-native speaker named The English Grammar (1688). The original book has 270 pages addressing grammar and dialogues and even incorporating a small dictionary. In the 119 pages addressed to grammar, he specifically focused on orthography and the pronunciation of English, as well as words forms and base paradigms. He believed that once the student had learned the fundamentals of spelling and sound systems of English, they would have a much easier time. Teaching the principles of pronunciation, grammar and spelling were fundamental to Miège as well as the teaching of phrases and dialogues. Some of these ideas were well incorporated into my preferred teaching approach. He also supported the idea of columns and braces to help understand visually and condemned the idea of learning a language leaving the grammar rules out in the beginning. Despite that, he allowed his students who were unwilling to learn grammar first, to memorize the texts before addressing the rules (Howatt, 1984, pp. 53-57).

Howatt continues his analysis into the eighteenth century. He states that something special happened during this time. The teaching of English outside Britain took off, creating the opportunity to develop different views on how to teach English as a second language. The Netherlands and France already had some sort of ESL teaching history, but in the second half of the XVIII century, English took a giant leap. The growing interest in Germany on the works of Shakespeare set the country into a frenzy over the English language and became a breakthrough for the development of the Grammar-Translation Method. One of the earlier German works was Johann König’s Volkommener Englischer Wegweiser für Hoch-Teutsche (1706), a book that included everyday dialogues and a how to write a letter. A good example of the great interest among German authors in English prosody and phonology is Eber’s Englische Sprachlehre für die Deutschen (1792). The appearance of a large number of grammars in this period led Johann Christian Fick, to write the first English teaching Grammar-Translation course in 1793, Praktische englische Sprachlehre für Deutsche beiderlei Geschlechts, nach der in Meidingers französische Grammatik befolgten Methode, published in Erlangen (Howatt, 1984, pp. 61-65, 132).

Another interesting aspect is that the first book to teach English in the Eastern hemisphere was published in 1787 in Serampore, India, and printed by the author John Miller. The Tutor (short name of the book) starts with the English alphabet, moving to pronunciation using a phonetic technique, and followed by a vocabulary list that avoids erudite words. The grammar focuses mainly on practical discussions that are closely related to trade. A great take from this book is that it includes writing, and not just copying from an English text. The goal was to make the students reflect upon each construction (Howatt, 1984, pp. 67-68).

According to Richards and Rodgers, the mid-nineteenth century basically dealt with grammatical issues. They used sample constructions to explain the grammatical rules of the language. Organizing L2’s morphology and syntax was the main focus of writers from this period. Oral and written exercises were almost non-existent. Karl Plötz is probably the most typical author of this time. In his textbooks, the only instruction was translation. Typical constructions used by Plötz, and quoted by Titone were “Thou hast a book. The house is beautiful. He has a kind dog. We have a bread [sic].” (Titone, 1968, p. 27) (Richards & Rodgers, 1986, p. 3).

The Classical Method of English Teaching in summary and all the described authors and methods have contributed to the so called Grammar-Translation Method, in which the main focus was reading and writing. This is a trend that, according to Richards and Rodgers, “dominated European and foreign language teaching from the 1840s to the 1940s” (Richards & Rodgers, 1986, p. 4). The integration movement between European countries opened opportunities for communication between citizens, demanding oral proficiency in the L2. By this, a market for books and phrasebooks that focused on conversation was created. These books were usually planned for private studies, but language teachers also addressed the way the L2 was being taught in public and private schools.

The Direct Method

Around the turn of the 19th century, a method arose that served to right the shortcomings of the grammar-translation method.

After reading “The Direct Method”, you can check important issues for ESL teachers on the section PDFs, and visit my channel on YouTube.

When the grammar-translation method’s deficiencies became clear, the direct method addressed those competencies hardly touched by its predecessor.

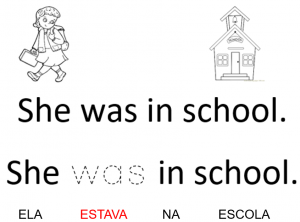

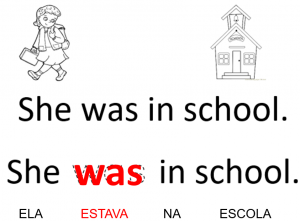

This method of teaching a language directly establishes an immediate audio visual association between experience and expression, words and phrases, idioms and meanings, rules and performances through the teachers’ body and mental skills, without any help of the learners’ mother tongue.

It’s the teaching method that puts grammar—its rules, morphology, syntax—at the forefront. Language is taught by analyzing the different elements of language and explicitly prescribing correct ways of combining those elements.

There are no grammar exercises, no committing of rules to memory, no lessons on how to write the plural form of a noun or how to conjugate a verb. That’s why it’s also known as the “anti-grammatical method.”

The direct method uses only the target language. the direct method is also known as “the natural method” because it looks to the process of first language acquisition to set the context and techniques for second language acquisition. When we learned our mother tongue, we didn’t go through grammar lessons and translation drills.

The teacher won’t be telling students about rules and such. Instead, you’ll let your students figure out the rules for themselves. The teachers’ job is to give students materials to piece together so they can connect the dots and discover the parameters for themselves.

Just as we acquired our first language through repeated exposure, so should it be in class. We didn’t memorize anything for our mother tongue, we simply acquired it through repeated exposure.

Students learn best when the teacher teaches them things that are only slightly beyond their reach. And helping them “get there” by giving them simple inputs that they can actually use to figure things out.

Let’s say that in a German class the teacher wants to teach the word for the color blue—a vocabulary lesson. Instead of using direct translation and writing on the board, “BLUE = BLAU,” the teacher makes things more fascinating.

Bring several objects of the color—perhaps a blue house, a blue shirt, a blue cap, a rose and lipstick. Every time you point to the objects, say “Das ist blau. Blau.” (This is blue. Blue.) Go through the different objects and keep on repeating “blau.” With repeated exposure, your students will soon get the point. To check for comprehension, point to an object of different color, say a yellow pen, and ask, “Blau?” The class should asnwer “Nein!” (No!)

To teach grammar rules, like how to form the plural of nouns. The teacher might bring two sets of pictures. One depicting lone objects, the other, depicting a group. The teacher holds the pictures side by side, clearly enunciating, for example, “car” on your right and “cars” on your left. Repeat this process for several pairs of pictures, emphasizing the “s” sound each time. Students will eventually pick up on the clues and figure out the rules for themselves.

Total Physical Response

Total Physical Response

Total physical response was developed by James Asher, a professor emeritus of psychology at San José State University. It attempts to teach language through physical (motor) activity. it draws on several traditions, including developmental psychology, learning theory, and humanistic pedagogy, as well as on language teaching procedures proposed by Harold and Dorothy Palmer in 1925.

After reading “Total Physical Response”, you can check important issues for ESL teachers on the section PDFs, and visit my channel on YouTube.

Total Physical Response holds that the more often or the more intensively a memory connection is traced, the stronger the memory association will be and the more likely it will be recalled.

Retracing can be done verbally (e.g., by repetition) and/or in association with motor activity. Combined tracing activities, such as verbal practice accompanied by motor activity, increases the probability of success.

In a developmental sense, TPR claims that speech directed to young children consists primarily of commands, which children respond to physically before they begin to produce verbal responses. It perceives adults should recapitulate the processes by which children acquire their mother tongue.

TPR shares with the school of humanistic psychology a concern for the role of emotional factors in language learning. A method that is lenient in terms of linguistic production and that involves gamelike movements reducing learners’ stress and creating a positive mood in the learner, will facilitate learning.

Asher’s emphasis on developing comprehension skills before the learner is taught to speak . This refers to several different comprehension-based language teaching proposals, which belief that

- (a) comprehension abilities precede productive skills in learning a language;

- (b) the teaching of speaking should be delayed until comprehension skills are established;

- (c) skills acquired through listening transfer to other skills;

- (d) teaching should emphasize meaning rather than form; and (e) teaching should minimize learner stress.

The emphasis on comprehension and the use of physical actions to teach a foreign language at an introductory level has a long tradition in language teaching.

Asher views the verb, and particularly the verb in the imperative, as the central linguistic motif around which language use and learning are organized.

TPR sees language as being composed of abstractions and non-abstractions.

- non-abstractions being most specifically represented by concrete nouns and imperative verbs. He believes that learners can acquire a “detailed cognitive map” as well as “the grammatical structure of a language” without recourse to abstractions.

- abstractions should be delayed until students have internalized a detailed cognitive map of the target language. Abstractions are not necessary for people to decode the grammatical structure of a language. Once students have internalized the code, abstractions can be introduced and explained in the target language.

This is an interesting claim about language but one that is insufficiently detailed to test. For example, are tense, aspect, articles, and so forth, abstractions, and if so, what sort of “detailed cognitive map” could be constructed without them?

Asher also refers in passing to the fact that language can be internalized as wholes or chunks, rather than as single lexical items, but he does not elaborate further on his views of chunking.

He sees a stimulus-response view as providing the learning theory underlying language teaching pedagogy. In addition, he has elaborated an account of what he feels facilitates or inhibits foreign language learning. For this dimension of his learning theory he draws on three rather influential learning hypotheses :

1. There exists a specific innate bio-program for language learning, which defines an optimal path for first and second language development.

2. Brain lateralization defines different learning functions in the left- and right-brain hemispheres.

3. Stress (an affective filter) intervenes between the act of learning and what is to be learned; the lower the stress, the greater the learning.

The general objectives of TPR are to teach oral proficiency at a beginning level. Comprehension is a means to an end, and the ultimate aim is to teach basic speaking skills. A TPR course aims to produce learners who are capable of communicating to a native speaker.

Total Physical Response requires initial attention to meaning rather than to the form of items. Grammar is thus taught inductively. Grammatical features and vocabulary items are selected not according to their frequency of need or use in target language situations, but according to the situations in which they can be used in the classroom and the ease with which they can be learned.

The criterion for including a vocabulary item or grammatical feature at a particular point in training is ease of assimilation by students. If an item is not learned rapidly, this means that the students are not ready for that item. Withdraw it and try again at a future time in the training program.

Asher suggests that a fixed number of items be introduced at a time, to facilitate ease of differentiation and assimilation. “In an hour, it is possible for students to assimilate 12 to 36 new lexical items depending upon the size of the group and the stage of training”.

The movement of the body seems to be a powerful mediator for the understanding, organization and storage of macro-details of linguistic input. Language can be internalized in chunks, but alternative strategies must be developed for fine-tuning to macro-details.

A course designed around Total Physical Response principles, however, would not be expected to follow a TPR syllabus exclusively.

We are not advocating only one strategy of learning. Even if the imperative is the major or minor format of training, variety is critical for maintaining continued student interest.

Imperative drills are the major classroom activity in Total Physical Response. They are typically used to elicit physical actions and activity on the part of the learners.

Conversational dialogues are delayed until after about 120 hours of instruction. Asher’s rationale for this is that “everyday conversations are highly abstract and disconnected; therefore to understand them requires a rather advanced internalization of the target language”.

Other class activities include role plays and slide presentations. Role plays center on everyday situations, such as at the restaurant, supermarket, or gas station. The slide presentations are used to provide a visual center for teacher narration, which is followed by commands, and for questions to students, such as “Which person in the picture is the salesperson?”. Reading and writing activities may also be employed to further consolidate structures and vocabulary, and as follow-ups to oral imperative drills.

Students have the primary roles of listener and performer. They listen attentively and respond physically to commands given by the teacher.

They are required to respond both individually and collectively, having little influence over the content of learning, since content is determined by the teacher, who must follow the imperative-based format for lessons. Students are also expected to recognize and respond to novel combinations of previously taught items.

It is the teacher who decides what to teach, who models and presents the new materials, and who selects supporting materials for classroom use. The teacher is encouraged to be well prepared and well organized so that the lesson flows smoothly and predictably. Asher recommends detailed lesson plans: “It is wise to write out the exact utterances you will be using and especially the novel commands because the action is so fast-moving there is usually not time for you to create spontaneously”. Classroom interaction and turn taking is teacher rather than learner directed. Even when learners interact with other learners it is usually the teacher who initiates the interaction:

Teacher: Maria, pick up the box of rice and hand it to Miguel and ask Miguel to read the price.

The teacher’s role is not so much to teach as to provide opportunities for learning. The teacher has the responsibility of providing the best kind of exposure to language so that the learner can internalize the basic rules of the target language. Thus the teacher controls the language input the learners receive, providing the raw material for the “cognitive map” that the learners will construct in their own minds. The teacher should also allow speaking abilities to develop in learners at the learners’ own natural pace.

In giving feedback to learners, the teacher should follow the example of parents giving feedback to their children. At first, parents correct very little, but as the child grows older, parents are said to tolerate fewer mistakes in speech. Similarly teachers should refrain from too much correction in the early stages and should not interrupt to correct errors, since this will inhibit learners. As time goes on, however, more teacher intervention is expected, as the learners’ speech becomes “fine tuned.”

Learning Strategy Training

Learning Strategy Training

Language learning strategies, are the conscious thoughts and actions used by learners to accomplish a learning goal. They are the specific initial steps of the whole vocabulary learning process. Quite simply, words learning strategies education is the operationalization and implementation of strategies for language skills development.

After reading “Learning Strategy Training”, you can check important issues for ESL teachers on the section PDFs, and visit my channel on YouTube.

Language learning strategies focus on attentiveness, vocabulary, speaking, reading, and writing, while experiencing words, learners deal with vocabulary learning problems in a organized manner and are successful in selecting appropriate strategies to complete a language-learning job, beginners may be less efficient at selecting and using ways of process.

Both type of learners, experienced and beginners, will need instructions on ‘how’ to use strategies efficiently to build up their terms learning and terminology performance. A effective way to steer learners into the use of learning strategies is to incorporate them into daily terminology lessons.

Once a learning strategy becomes familiar through repetition, it might be used with some automaticity by most learners. According to some scholars, LLSI is a key way for teachers to help learners learn autonomously.

With strategy training, students can understand how to study a second language, enhance their learning and examine their performance, becoming more alert to what helps them learn the vocabulary they are studying.

Language learning strategies instructions can be educated in at least three different ways; awareness training, onetime strategy training and long term strategy training.

- Awareness training is when participants become aware of the words learning strategies and the way these strategies can help them complete various jobs. This training should be fun and motivating so that members can broaden their knowledge of strategies. Participants can be educators, students or other people interested in words learning techniques.

- One time strategy training involves learning and practicing a number of strategies with actual learning tasks. This kind of training normally gives the learners information on the value of the strategy, when it could be used, how to put it to use and how to evaluate the success of the words strategy. This training is well suited for learners who have a dependence on a specific and targeted strategy that may be taught in one or a few consultations.

- Long term strategy training consists of learning and exercising strategies with real language tasks. Students learn the significance of a specific strategy, when and the way to use it, how to screen and examine their own performance. This strategy is most probably to more effective than onetime training.

LLSI Model by Oxford

Oxford’s eight-step model for strategy training targets the teaching of learning strategies. It is especially helpful for permanent strategy training. It can even be designed for one-time training by selecting specific items. The first five are planning and prep steps, while the previous three involve doing, analyzing and revising the training.

- Step 1: Determine the Learners’ Needs and the Time Available: The initial step in a training program is to consider the needs of the learners and determine the amount of time necessary for the experience. Consider first who the students are and what they need. Are they children, teenagers, graduate students or parents in continuing education? What exactly are their durability and weaknesses? What learning strategies have they been using? Is there a gap between the strategies they have been using and the ones learners think they need to learn? Consider also how much time learners supply for strategy training so when they might do it. Are students pressed for time or can they work strategy training in with no trouble?

- Step 2: Select Strategies Well First: select strategies that are related to the needs and characteristics of learners. Take note especially whether there are strong ethnical biases in favor or against a specific strategy. If strong biases can be found, choose strategies that do not completely contradict the particular learners already are doing. Second, chose several kind of strategy to teach. Decide the kinds of suitable, mutually promoting strategies that are important for students. Third, choose strategies that are generally useful for some learners and transferable to a variety of terminology situations and jobs. Fourth, choose strategies that are easy to learn and valuable to the learner. In other words, do not include all easy strategies or all difficult strategies.

- Step 3: Consider Integration of Strategy Training It is most beneficial to assimilate strategy training with the duties, targets, and materials used in the regular dialect training program. Efforts to provide detached, content self-employed strategy training have been reasonably successful. Learners sometimes rebel against strategy training that’s not sufficiently associated with their own terms training. When strategy training is integrated with terms learning, learners understand better the way the strategies can be used in significant, meaningful context. Meaningfulness helps it be easier to keep in mind the strategies. However, additionally it is essential to show learners how to copy the strategies to new tasks, beyond the immediate ones.

- Step 4: Consider Motivational Issues Consider the sort of motivation instructors will build into an exercise program. Decide whether to give grades or incomplete course credit for attainment of new strategy. If learners have been through a strategy assessment phase, their fascination with strategies is likely to be heightened. If a instructor explains how utilizing a good strategy can make terms learning easier, students could be more interested in engaging strategy training. Another way to increase motivation is to let learners have some say in selecting the vocabulary activities or tasks they’ll use, or let them choose strategies they’ll learn. Language teachers have to be very sensitive to learners’ original strategy choices and the motivation that propels these personal preferences. Which means that teachers should cycle in very new strategies carefully and slowly but surely, without whisking away students’ ‘security blankets’.

- Step 5: Prepare Materials and Activities The materials that can be used for strategy training are handouts or handbook. Learners can also create a strategy handbook themselves. They can donate to it incrementally, as they learn new strategies that confirm successful to them.

- Step 6: Do “Completely Informed Training” Make a special point to inform the learners as completely as is possible about why the strategies are essential and how they can be found in new situations. Learners have to be given explicit possibility to measure the success of their new strategies and exploring why theses strategies may have helped. Research shows that strategy training which totally informs the learners, by indicating why the strategy is useful and how it can be transferred to different responsibilities, is more lucrative than training that will not. Most learners perform best with completely educated training. In the rare situations, when informed training proves impossible, more delicate training techniques might be necessary. For example, when learners are through ethnical affects, new strategies have to be camouflaged or created very gradually, combined with strategies the learners already know and like.

- Step 7: Measure the Strategy Training Learners’ own reviews about their strategy use are area of the training itself. These self assessments provide practice with the strategies of self monitoring and self evaluating, after and during working out, own observations are of help for evaluating the success of strategy training. Possible standards for evaluating training are job improvement, standard skill improvement, maintenance of the new strategy, copy of strategy to other relevant tasks and improvement in learner’s frame of mind.

- Step 8: Revise the Strategy Training The evaluation phase (Step 7): will suggest possible revisions. This leads right back to Step one 1, a reconsideration of the characteristics and needs of the learners in light of the cycle of strategy training that has just happened.

How to Integrate LLSI into Terms Classroom?

LLSI may be included by teachers into their daily language school room. LLSI is needed to enhance listening, speaking, reading, or writing course in words learning and coaching.

There are three steps in applying LLSI in the class regarding to Clouston (1997).

- Step 1: Review Your Coaching Context By watching students’ behavior in class, instructors will be able to see what LLS they are using. Talking to students informally before or after school, or more formally interviewing go for students about these topics can provide a lot of information about one’s students, their goals, motivations, and LLS, and their understanding of the particular course being taught. Teachers should review their own teaching methods and overall school room style. The best way to do so is to check out their lesson ideas and identify if indeed they have incorporated other ways that students can learn the words.

- Step 2: Concentrate on LLS in Your Teaching Focus on specific LLS in your regular coaching that are relevant to your learners, your materials, and your own coaching style. LLS can be utilized in understanding how to write or on paper, and completing the gaps with other LLS for writing that are neglected in the text but would be especially relevant for your learners. Provide students with opportunities to use and develop their LLS also to encourage more unbiased language learning both in course and in out-of-class activities for your course.

- Step 3: Reflect and Encourage Learner Reflection In utilizing LLSI, purposeful tutor reflection and stimulating learner representation form a required third step. On a basic level, it pays to for teachers to think about their own positive and negative experiences in vocabulary learning. After every course, one might reflect on the effectiveness of the lesson and the role of LLSI within it. As well as the teacher’s own reflections, it is essential to encourage learner representation, both after and during the LLSI in the class.

When including strategies based mostly instruction in another language curriculum, it’s important to choose an instructional model that presents the ways of the students and raises awareness of their learning personal preferences; teaches them to recognize, practice, assess, and transfer ways of new learning situations; and promotes learner autonomy to permit students to continue their learning after they leave the terminology classroom.